When you hear the word library, what is the first thought or image that comes to mind?

I picture shelves upon shelves of books. I see people of all ages and backgrounds. I see the elusive second floor of the main library in my hometown, which seemed mysterious to my child eyes. I smell books – that good, old book smell. I hear copy machines and fingers typing furiously on keyboards; young children shrieking during story time and people asking librarians every question under the sun. More than anything, I see visions of myself at every age, sitting on the floor and poring over books.

One thing I never picturing when hearing the word library? FIRE.

On April 29, 1986, the main branch of the Los Angeles Public Library caught fire. It destroyed or damaged over 1 million books and wreaked havoc on a central institution in the city. The fire raged for hours, with firefighters from around the city called in to tame the blaze. It took them more than 7 hours to extinguish the fire. It’s something I cannot even imagine witnessing.

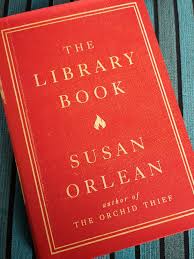

In The Library Book, Susan Orlean investigates this event. But her book explores even more. From the history of the Los Angeles library to the current administration of one of the largest library systems in the country; to the societal impact and importance of libraries in society; on the evolution of libraries in the digital age; to details about the suspected arsonist and then arson itself; Orlean gives us a lot of information to ponder.

In The Library Book, Susan Orlean investigates this event. But her book explores even more. From the history of the Los Angeles library to the current administration of one of the largest library systems in the country; to the societal impact and importance of libraries in society; on the evolution of libraries in the digital age; to details about the suspected arsonist and then arson itself; Orlean gives us a lot of information to ponder.

My draw to this book was the event itself because I had never heard of this infamous fire. I would have been too young to see it on the news, but even my older relatives were not aware of it. The 1980s were the beginning of the 24-hour news cycle. This surely would have made headlines, right?

Orlean answers that early in the book: this was the same time as the nuclear plant explosion at Chernobyl. She writes, “The books burned…while most of us were waiting to see if we were about to witness the end of the world.” This was one of the worst library fires the world barely acknowledged.

The recovery efforts were astounding. If books were not burned or destroyed, they were water-logged from the massive amounts of water needed to staunch the blaze. The books had to be frozen before mold could set in, then specially dried before determining if they too were lost. The books that were left untouched were stored in warehouses around the city during the building repair. The hundreds of employees from main branch were left in shock; without a library, what would they do?

Despite the daunting task of repair and restoration, the library survived.

The structure was largely intact and fixable. The entire city seemed to pitch in time, warehouse space, freezer storage, work, and money to rebuild. Books were replaced by massive fundraisers and efforts from celebrities and politicians alike; the library also sold its air rights to developers to raise the estimated $14 million in lost books and works. It took time and effort, but the library reopened on October 3, 1993.

As I said, this book was about more than the fire.

Part of the challenge of reading this book was all the information. The chapters bounce back and forth between history, present day, heavy facts, and personal anecdotes from the author. Some parts were fascinating: I enjoyed her time with John Szabo, the current city librarian. He oversees every branch and employee; his initiatives to engage the community and continually improve library and reader relations are impressive. With every interview with a current or former library employee, I found myself wishing I could be one. Gretchen, another book club member, shared my thoughts on this matter.

Yet some parts were a struggle to get through. The long history of city librarians, while interesting to some, felt extraneous to the book. There was much information about Harry Peak, the only suspect in the arson. It sometimes felt like one was reading a biography of a man who never even had charges pressed against him for the crime. It felt like an idea for a story that got away from the author, and Susan Orlean even admits that the original idea for the book was to write about the daily life of a city library.

With this sentiment in mind, I feel that Orlean wrote the book that she set out to write. The fire and the events surrounding it are an intriguing element; the history is important. But the real success of The Library Book is in the stories and anecdotes about the library, its employees, and the people it serves. Libraries are an institution that nearly everyone can identify with, and they are collective points for all members of the community.

I walked away from this book with a head full of information; a new appreciation for libraries and their employees; and nostalgia for that library in downtown Davenport that helped shape my love for reading and books.

Join us next month as we read The Silent Patient by Alex Michaelides.