I enjoy reading stories that are fiction yet based in real life. The events may be altered, and the names may be entirely fake. The settings and the plot are at the discretion of the author, who can and will spin a tale that enchants the reader. But I like knowing that under this fictional world, there is truth.

In A Woman Is No Man by Etaf Rum, that is what we have: a fictional story of a multi-generational Palestinian-American family and particularly of the women in the family. Their lives are difficult. Their struggles may seem foreign to us who live outside of this culture. We read about their lives in and out of America at a distance, all the while knowing that for some women, this is a reality.

In A Woman Is No Man by Etaf Rum, that is what we have: a fictional story of a multi-generational Palestinian-American family and particularly of the women in the family. Their lives are difficult. Their struggles may seem foreign to us who live outside of this culture. We read about their lives in and out of America at a distance, all the while knowing that for some women, this is a reality.

We begin with Isra in 1990.

She is a 17-year-old Arab girl living in Palestine with her parents and brothers. She is meeting with suitors and waiting for her parents to arrange her marriage. While this sounds strange to some of us, this is standard in her culture. Sons are valued for their future contributions to their families; daughters are seen as a burden and quickly married off. A woman is no man.

This does not mean that Isra loves the idea of marrying a stranger. She questions her mother about love and choices. Her mother responds with this:

There is nothing out there for a woman but her bayt wa dar, her house and home. Marriage motherhood – that is a woman’s only worth.

Could you imagine being presented with this stark fact? As a mother of daughters and a woman myself, I could not imagine living in a world where these were my only roles in life. This statement took me aback and gave me pause.

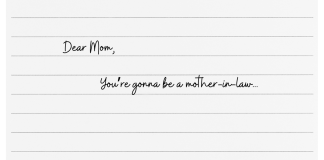

Regardless of her personal feelings, her marriage is arranged by her parents and in-laws to a Palestinian-American named Adam. The marriage happens quickly, and Isra is off to America to start her new life. She lives with her new family in Brooklyn.

This is where we meet our next prominent character, Fareeda.

Fareeda is Adam’s mother. She is overbearing, demanding, and often appears cruel to Isra and her own daughter Sarah. Fareeda has been and is a traditional Arab wife, and that is what she expects of Isra. This means she is to be subservient to her husband and all men, to cook and clean, and to bear sons. We see hints of Fareeda’s own past and how it has shaped her life, but she is ultimately rooted in the same culture and beliefs.

And she firmly repeats the theme and title of this book: a woman is no man.

The book is told in excerpts from Isra, Fareeda, and Deya. Deya is the oldest of Isra’s four daughters. The story jumps back and forth from the 1990s to the late 2000s, depending on who the narrator is in that chapter.

We learn that Isra struggled in her marriage and in America. With the birth of every daughter, she is shamed by Fareeda and made to feel like a failure. She is isolated and alone. She finds some comfort in books (a hidden habit), but she is tired and depressed. No one talks about this though. This and other things.

I thought about how to address the abuse and mistreatment of women in this book in a delicate way.

It is something that was difficult to read and to think about discussing. But I wanted to honor the author, who grew up in this culture herself and left an arranged marriage. In an interview with NPR, Etaf Rum states, “One of those struggles was confirming stereotypes about Arab people and the Arab community, stereotypes that include oppression, domestic abuse, terrorism. And so that kind of hindered my ability to express myself freely, without fear, in the beginning when I was writing the novel.”

Adam is overworked. He is also an alcoholic and abusive. Isra accepts that this is her lot in life, and it is confirmed by her mother-in-law and her memories of her own parents. There is no reason for the abuse; there never is. Adam is also frustrated with his life. Yet there are things, like physical abuse and drinking, that are acceptable for men and not for women. When it is questioned, the same answer is given: a woman is no man.

We learn much about the family from Deya’s perspective.

She is at the same precipice that her mother faced, although it is 2008 and she lives in Brooklyn. Her grandparents want her to get married and settle into her place. Deya wants the opposite. She wants the freedom to choose naseeb or destiny. She wants to attend college. She wants to know more about her parents and especially her mother, who we learn died years ago.

It is through her eyes that we begin to see the cracks in her parents’ marriage. We see how Fareeda’s cruelty and strict adherence to their Arab customs are rooted in fear. We learn that there are secrets and shame buried deep in their family. And we see that maybe, just maybe, she and her sisters could find their voice and make their own choices.

There are so many things that Deya learns as she grows into her own voice and person. I would never reveal a spoiler! I can say that this is gleaned eventually: a woman is no man. But that does not mean that a woman has to be inferior to a man. Culture and family are important, but perhaps progress and growth are even more so.

Thanks for reading with us last month! We are reading

Thanks for reading with us last month! We are reading