At some point in our education, we learned about slavery in the United States.

We learn about the slave trade. We discuss what life was like for most slaves living in the South. We hear names of famous abolitionists like Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglas, and more. We know what the Underground Railroad was and how important the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation were.

But what about Juneteenth?

Juneteenth is the oldest official celebration of the end of slavery. On June 19th, 1865 Union soldiers landed in Galveston, Texas to bring word that all slaves were now free. Even though the Emancipation Proclamation was signed into law by President Lincoln on January 1, 1863, it took two and a half years for freedom to become a reality to the entire nation. You can read more about that here. Since then, June 19th has become an internationally recognized day of observation, commemoration, education, and celebration.

There are many famous abolitionists whose stories are taught in schools today. But did you know that abolition sparked the women’s rights movement? It is frustrating and disheartening to know that the roots of Black Lives Matter is older than feminism, yet the fight against racism has much further to go.

By the 1840s, black and white women served as antislavery lecturers, editors, fundraisers and organizers. Slaveholders fumed at women’s activism. The Southern Literary Messenger referred to abolitionist women as “politicians in petticoats” who needlessly stirred up trouble on the slavery issue. Yet even some male abolitionists were chagrined by women’s activism before the Civil War. In 1840, the American Anti-Slavery Society divided over women’s role in the movement, with some conservative reformers refusing to support female lecturers or leaders. Nevertheless, women’s activism grew more intense over the next two decades, making the abolitionist movement a much stronger and more ramifying entity on the eve of the Civil War. (source)

In honor of Juneteenth, we wanted to highlight female abolitionists that were part of the anti-slavery movement. Some you may have heard of; others you may be reading about for the first time. This is not a comprehensive list either – please share with us any other female abolitionists that we can learn more about. But as moms and female leaders in our community today, we can learn much from these women and the impact they made for justice and equal rights.

So read, learn, and celebrate Juneteenth with us and the world. It’s an important day in our country’s history!

Mary Prince (1788-1833 est.)

Born into an enslaved family in Bermuda, Mary Prince suffered a horrific early life under multiple slave owners. In 1828, she moved to England with her owners; it was there that she was able to escape and find freedom. She had to remain in England to maintain her freedom, leaving behind her husband in Antigua. But she used that freedom to become an abolitionist.

Mary worked with the Anti-Slavery Society and with Thomas Pringle, a fellow abolitionist. According to The Abolition Project, “She became the first woman to present an anti-slavery petition to Parliament and the first black woman to write and publish an autobiography, ‘The History of Mary Prince: A West Indian Slave ‘.” These brought forth the injustices and treatment of slaves to the British people, forcing them to confront these horrors. Little is known of her life after 1833, but her work and her words are not forgotten.

Maria Stewart (1803-1879)

Maria Stewart was an abolitionist, women’s rights activist, and essayist. She even wrote pieces for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. But what she is most known for is her public speaking. She was the first black woman to speak in public on political issues (no small feat for any woman at that time). She delivered four speeches in Boston in the early 1830s about sexism, the lives of freed and enslaved African-Americans, equal access to education, and religious perspectives.

Although not all her words were received positively, it was her courage to speak at all that is most inspiring. However, she removed herself from public speaking in 1833 and remained an educator and a lecturer for the remainder of her life. She taught at schools in New York City, Baltimore, and Washington D.C. before taking a head matron assignment at the Freedman’s House. She never stopped writing, speaking, and advocating for equal rights for all people.

Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793-1880)

Born to a Quaker family in Massachusetts, Lucretia Mott attended boarding school in New York where she learned about the horrors of slavery. She also saw the inequalities between male and female instructors, and became determined to put an end to social injustice at a young age.

Along with 30 other female abolitionists like Mary Ann M’Clintock, Mott organized the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. She was selected to act as a delegate from that organization to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840 in London. However, women were not allowed to participate, and that sparked Mott along with others to hold the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848.

Throughout her life, Mott continued to be an active voice in abolition and women’s rights. She became the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, which sought equality for both African Americans and women. Her life was honored by African Americans in many cities at the time of her passing in 1880.

Mary Ann Shadd Carey (1823-1893)

Born to free African Americans in Delaware when it was a slave state, Mary Ann Shadd Carey became an activist, teacher, writer, and lawyer. The Shadd family participated in the Underground Railroad, helping those enslaved escape to freedom. But when the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850 making it legal for escaped slaves living in free states to be returned to enslavement and punishing those who helped, Carey escaped to Ontario, Canada.

In Canada, then Mary Ann Shadd met and married Thomas Carey and opened an integrated school for black and white children. “To promote immigration to Canada, Shadd publicized the successes of black persons living in freedom in Canada through The Provincial Freeman, a weekly newspaper first printed on 24 March 1853. This made Shadd, who was one of the first female journalists in Canada, the first black woman in Canada and North America to publish a newspaper” (source). After her husband’s passing, Carey moved back to the US, helping recruit soldiers for the Union Army.

After the Civil War, Carey enrolled in the first class of Howard University Law School and became an activist and writer for a local African American newspaper in Washington D.C. She was one of the first black women to complete a law degree. Carey was also a founder of the Colored Women’s Progressive Franchise Association, and became involved in the National Woman Suffrage Association.

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896)

Best known for writing Uncle Toms’ Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe was born into a prominent family in Connecticut, Stowe was educated at Hartford’s Female Seminary which exposed her to many of the same courses her male counterparts received. She married Calvin Stowe in 1836, who encouraged her writing. They had seven children together and weathered many storms.

Stowe’s turning point in her personal life and in her writing came in 1849 when her son died in a cholera epidemic. “She later said that the loss of her child inspired great empathy for enslaved mothers who had their children sold away from them. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which legally compelled Northerners to return runaway slaves, infuriated Stowe and many in the North. This was when Stowe penned what would become her most famous work, the novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (source).

Stowe used her widespread fame as a platform to fight for the end of slavery. She toured internationally speaking about her book and donating proceeds to anti-slavery causes. During the Civil War, Stowe was one of the most prominent and visible writers. She had many critics who published pro-slavery satires of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and insisted her portrayal of slavery in the book was inaccurate. But none of that swayed her mission to see slaves freed.

Popular folklore quoted President Abraham Lincoln saying, “So you’re the woman who wrote the book that started this great war” upon his meeting Stowe in 1862. The historical accuracy of that has been called into question, but it is inarguable that Stowe had a major influence on the cultural change that led to the political movement of abolition.

Sarah Parker Redmond (1824-1894)

Born to free and economically secure parents, Sarah Parker Redmond’s family was rare for African Americans of the day. Redmond was an outspoken advocate of abolition, and gave her first speech at only 16 years old. She was eloquent and never used notes, but always brought her audience to tears. Her family traveled around Britain, Scotland, and Ireland where she gave 45 lectures petitioning the rights of slaves in the US.

After the Civil War, at the age of 40, Redmond moved to Italy where she studied and practiced medicine and is reported to have been Florence Nightingale’s model of medical care and training.

She remained in Italy until her death, but was never silent about anti-slavery causes, and entertained many abolitionists like Fredrick Douglass on their European tours.

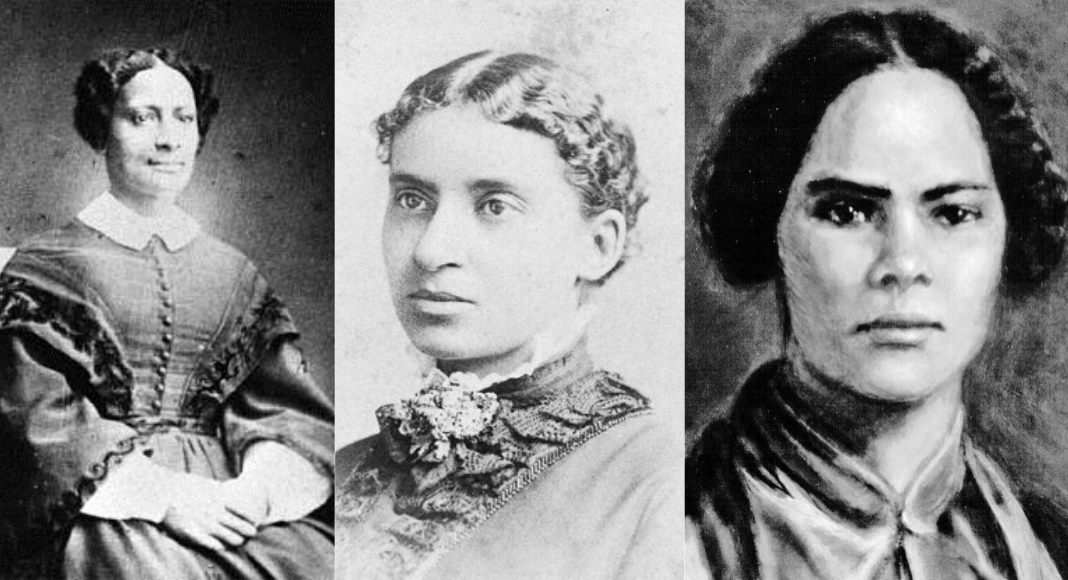

The Forten Sisters: Margaretta Forten (1806-1875), Harriet Forten Purvis (1810-1875), and Sarah Forten Purvis (1814-1883)

The Forten family was a multi-generational African-American family with roots dating to the founding of Philadelphia. They were wealthy, educated, and prominent in the country and in society. The family used their wealth and influence to establish several anti-slavery and African-American societies; some members were conductors for the Underground Railroad.

Here are three members of the family that worked for equal rights and treatment:

Margaretta Forten was an abolitionist and a suffragist. She never married, choosing to dedicate her life to education. She even opened her own school in 1850.

She campaigned for women’s rights and equality as well as social reform. She toured with suffrage groups, gave speeches, and participated in petition drives. She was also an officer of the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, which was founded by her father James Forten. Due to ill health, she was not as active as her sisters; she died in 1875 due to pneumonia.

Harriet Forten Purvis was also a staunch abolitionist. She married Robert Purvis in 1832, a member of another prominent and abolitionist family. They had eight children, but motherhood did not stop Harriet from campaigning for the anti-slavery movement. She frequently attended conventions with her husband and was an active participant. Later, she would also become a suffragist and lectured on black suffrage.

Most notably, Harriet and Robert were conductors on the Underground Railroad. Their house was a safe haven for those traveling north to escape slavery. They also entertained other leading abolitionists including William Lloyd Garrison and John Greenleaf Whittier. Together, they continued to help the enslaved and the freed to live and create a better world.

Sarah Forten Purvis was a writer, activist, and abolitionist. She married Joseph Purvis (brother to Harriet’s husband) and had three children. They also continued to work with his family in the anti-slave movement. Along with her sisters, she was a member of the Female Literary Association, a Philadelphia based African-American women’s group founded in 1831. This group aimed for improvement in moral and literary pursuits.

Her poetry was very popular during this time; one was even adapted into the song “The Grave of the Slave” by Frank Johnson. She also wrote numerous letters and articles for The Liberator under a pseudonym. As her sister and various members of her family, she campaigned against slavery and for social reform her entire life.

Charlotte Forten Grimké (1837-1914)

Daughter of Robert Forten and Mary Wood, Charlotte was the niece of the Forten sisters and a member of this prominent activist family. Her mother died in 1840, and she was cared for by many members of the family. She was the first black pupil at the Higginson School for Girls in Philadelphia; she went on to attend the Salem Normal School as well. She remained in the city even after her father moved the family to Canada after the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850.

Charlotte was a teacher, writer, and abolitionist. Her most notable teaching assignment was as a teacher of freed slave children. In 1862, she moved to St. Helen’s Island off the coast of South Carolina. It was minimally guarded by Union soldiers, and the threat of attack by the Confederacy and pro-slavery citizens loomed large daily. But Charlotte educated 140 freed children in an old Baptist church, even carrying a pistol with her for her protection.

She married Francis Grimké in 1878, a law student and a Presbyterian minister. Charlotte worked with him in his ministries and his church, which he used to educate and promote civil rights. She continued to fight for education and equality for all African-Americans for the rest of her life.

![Getting Brave About [Solo] Adventures With My Kids](https://militarymomcollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/221A0095-218x150.jpg)